I’m really pleased that the following piece about how to write about “unbearable experience” has just been published in The Bellingham Review. It’s also about why I chose to use fantastical elements in writing Growing Up Golem.

When I set out to write a memoir about my parents 16 years ago, one of the things that stymied me was early feedback from my peers that the content was “too unbearable” to read about.

It was indeed difficult to be my parents’ daughter. My father hit me a lot. He was also remote and didn’t often speak, and my mother encouraged my sisters and me to make fun of him and call him names, which often resulted in him hitting me more. Despite this ugly bit of manipulation, my mother was nurturing in some other ways – she always fostered my love of learning and books, and continually stimulated my mind. Yet she also would parade naked in front of me, or in flimsy panties and bras, and force me to tell her she was sexy and that I loved and adored her more than anyone.

I didn’t think my parents were too unbearable to read about, but would my readers? An even more compelling issue for me was that I wanted to capture the “uncanny” feeling I had always had of being my mother’s puppet, or her creature (like a magician’s familiar, or something she had created in a laboratory, to experiment on with different stimuli or provocations). How could I write about this when, in the strictest sense, it wasn’t “true”? That is to say, it was truly my feeling, it was indeed what it had subjectively felt like, but my mother wasn’t actually a magician, and I wasn’t actually her homunculus.

Without the magic, however, there was no understanding the frozen way I had lived my life, as if completely separated from my own will and desires, or the fact that I’d never had a long-term relationship till after she died — as though forbidden or prevented by a mysterious spell that destined me for her alone.

Then I remembered that my mother had actually told us she could do magic – a mixture of Jewish magic from the Kabbalah and pagan European magic from Romania, which she claimed she had learned as a child from her grandparents. In fact, up till early adulthood, at least one sister and I had believed that she could actually practice this magic (not to the extent of making golems, but we believed that she could, as she said, foretell the future and interpret dreams).

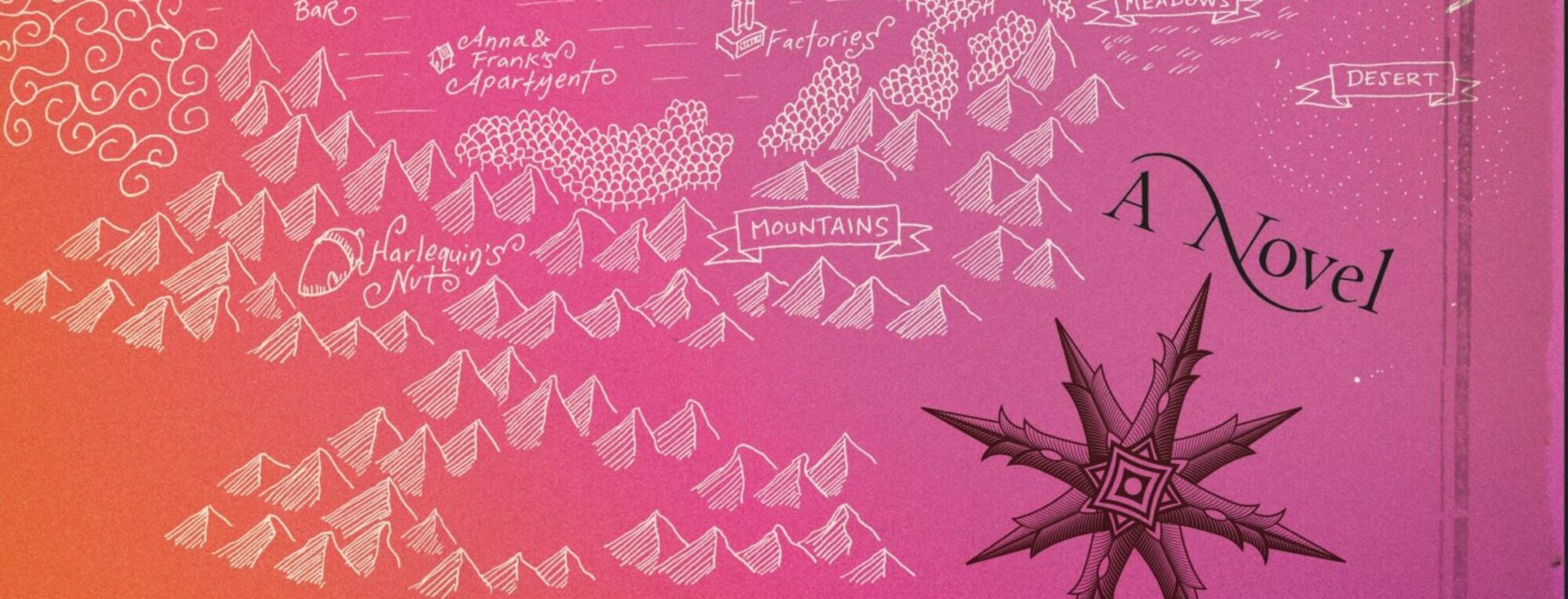

I decided to use this factoid, with a twist, as the controlling metaphor for the memoir. The twist would be that I would write the book as though my mother really WERE a powerful Kabbalistic magician. And I would combine memoir with fantasy and write the thing as though, instead of giving birth to me, my mother had created me by magic as her own personal golem, an animated clay servant out of Jewish legend. Every statement in the memoir would be true, except those involving magic or other fantastic activities.

This way, I wouldn’t have to let fiction writers have all the fun, but could actually make use of all the richness of myth and archetype in telling my life story. How could I turn myself from a magic puppet under a lifelong spell, into a human being? That would be the question of the book.

It might also be a way to make my father’s physical abuse, my mother’s (nonphysical) sexual and emotional abuse, more bearable for the reader to come on an extended journey with me through it. The light coat of fantasy would be one way of “tell [ing] it slant.”

Like this:

Like Loading...