-

This is Part 3 of my memoir in progress, Jailbreak. It’s a memoir set almost entirely within my own mind, where all the different characters are parts of me. You can find parts one and two here and here.

The harlequin moves through the quiet streets, body like an acrobat. Like a soft snake, like water, effortlessly, as if tumbling, unseen unless he wants to be. He moves through the tourist crowds around the plaza, he slips past cops, he slides into the jailer’s ugly living quarters to observe my hero:

Even lying in bed the jailer is rigid, his face is tensed and white. His ears are live for the threat, he cannot stop listening. His shoulders are taut as he tries to see if he can hear the whores outside the window, their possible cavorting. He projects his awareness out the window, wishing his ears were very long and he could stick them out into the night and have them reach, reach into iniquity and monitor it at every moment.

He hears nothing.

The harlequin pirouettes over to the jailer’s bony body and smiles at him, unseen. He straddles him on the iron bed and sweetly thumbs his nose.

***

I have no idea where the harlequin came from.

I can’t even say how long he’s been with me. From birth, I would have said, but I don’t know if I’ve been able to escape that long.

I remember at age 5 the yeshiva principal said on the PA system that one of us had done something terrible to the school bathroom and if we were the one who had done it, the school would know.

I was scared. Even though I hadn’t done anything to the school bathroom, I was afraid that somehow the school knew that I had.

I went home and asked my mother if the yeshiva had called.

***

Did the harlequin join me at age 8? At age 12?

When I’m on the cusp of changing, at age 12, I stand in the elevator of our apartment building in Coney Island with a magic marker, terrified by my own capacity to do evil. The elevator of our housing project is yellow and my marker is blue. And I make a mark with it on the elevator, because I am an evildoer.

***

The harlequin whirls through my brain, I can barely see him. He is lying to my mother, telling her he loves her beyond anyone, beyond anything, for all time. He tells her this because she forces him. But also because it’s better to lie, to turn colors, than to stand there and be punished and to suffer.

***

The jailer speaks:

Who was that?

I was being rubbed all over with oil. They were teasing me with long feathers.

So many of them were touching me. Then her big hands came and it was only her.

***

See the harlequin lying his head off. See him going through walls. See him getting me the hell out of there.

***

“Sit down RIGHT FUCKING NOW and write your book!”

Who is this part of me who orders all the other parts around like it was some kind of fucking monster?

Shut up and write.

***

The harlequin moves through the soft fields, lands empty of everything but alfalfa and barley. Wildflowers under his feet reminding him of the seeds he planted long ago, everywhere. Some things take a long long time to bloom. There is an abandoned gas station, a big oak, shanties and a hanging tree. He will go where he needs to go, anyplace that souls are caged. Bees move around the terrible little buildings where hundreds squeezed into the spaces meant for five.

He finds the children hiding in the crawlspace and sends them leaping over the field.

***

The jailer visits the harlequin in prison.

Now the harlequin is a tall young man with blonde hair down to his waist, vines curling around his neck and sliding down his whole sweet body. He is wearing a dress.

The jailer comes in with two guards and addresses his victim:

“You’re not impossible to look at.”

The harlequin says, “The god gave me my looks.”

The jailer: “You know what they say happens to effeminate men in jail.”

The harlequin: “Nothing will happen to me. I am in charge of whoever touches me.”

The jailer: “Your rot will not infect us!”

***

So, all that was more or less from The Bacchae, a play that has been performed many times in my own mind. But when The Bacchae‘s not playing, the harlequin has short dark hair or a shaved head, he wears pants or he is naked like the elves who help the shoemaker. He blends into his surroundings so well he’s hard to see. Or he is hard to see because he moves so quickly. Or his nude body is dark in the darkness. Or on a gray day he’s the color of water. Or if you see him in the sun, he’s colored like white light, all the colors together.

***

Who is the harlequin?

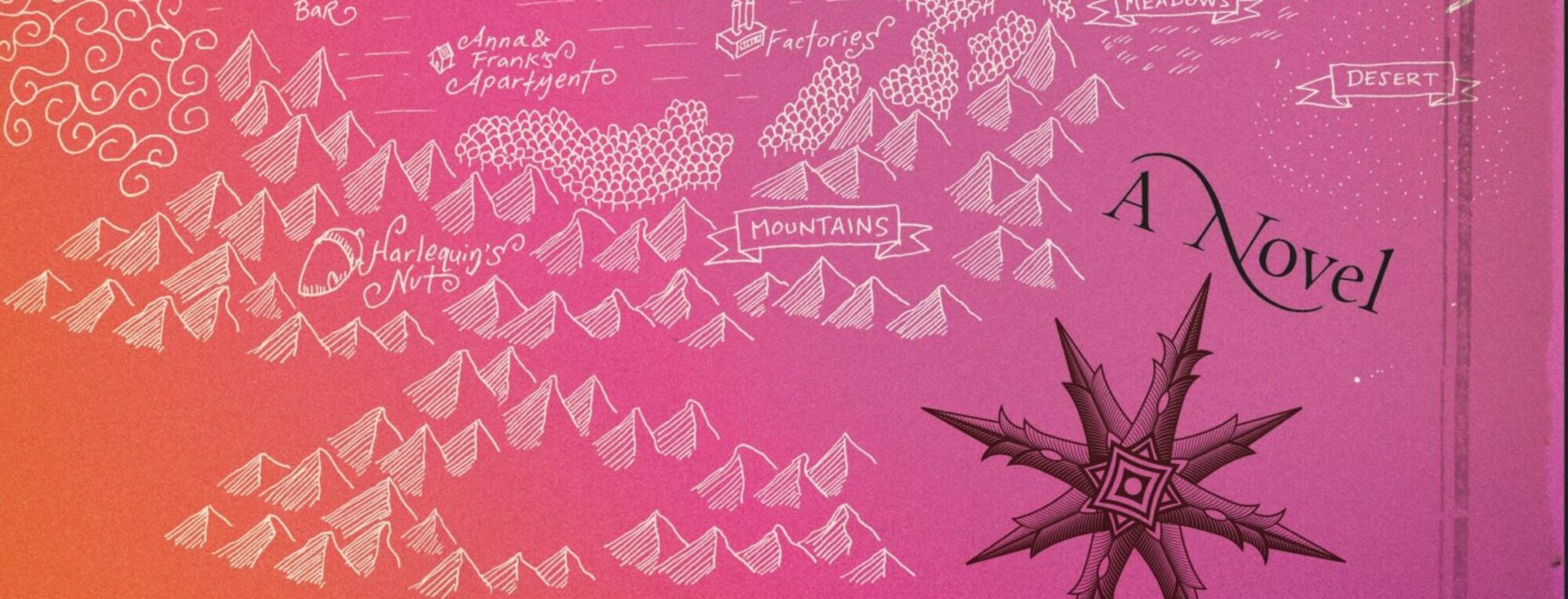

Let us spy on him at home, something no one else has done to date. His home is a black cave. There are no windows. The cave is round, like a nut. Huh, maybe the harlequin lives in a nut. It is also a Faraday cage.

A Faraday cage is an enclosure that prevents electromagnetic energy from getting in. It is not, properly speaking, a cage but a protected sphere. Nothing can hurt him here.

The harlequin speaks: I’m in my nut. The walls are beautiful and black, and I can see nothing. There is nothing to bother me. The black walls shine. There are no doors. Where I live is like a jewel.

In his round home, the harlequin lies gloriously naked and spreadeagled. There is just enough room in his shining black jewel to stretch out his arms and legs in every direction. He believes he draws energy into him from the universe, but in fact energy is precisely what cannot get inside these walls. There is also no food, there is no water, and there is not a soul to talk to. There is not even a bed. All it is is a round box.

***

When I’m in fifth grade, I have a recurring fantasy:

First my eyes pop off, then my nose. Then all my teeth pop out, softly and easily. There is no violence or sickness to any of this, only sweet relief.

Then my ears come off. It is so peaceful. Then I put my head under a hill, forever.

***

Starring as Dionysus in The Bacchae, the harlequin spends less than 15 minutes in the jailer’s cell. The prison crumbles from the ground up, earthquake splits the stone floor and the walls tumble. The harlequin elegantly steps out of the mess

***

I’m just seven hours old

Truly beautiful to behold

And somebody should be told

My libido hasn’t been controlled

You know nothing about me, Minkowitz. Or you do know but you’ve forgotten: it’s a long time since you were 12, or 15.

I am delicious

I am seditious

super nutritious

super pernicious

I have diamond hoops in my ears and I’m 7 feet tall.

I’m just a sweet transvestite from Donna’s brain, and I am the motherlode, baby.

I have always been here feeding you.

***

He has been here, a wall of fruit and water, a rising wave of wine, since I turned 15. He has shown me storehouses and greenhouses, he has been the corn secretly growing, the peach and walnut trees rising up to take care of me, he has been the milk and honey.

What, are you afraid you’ve wandered into the wrong narrative? Are you afraid I’m talking about religion now?

The god inside me is part of me.

***

I have a wave of power inside me

I have a wave of fruit

I think I can be 300 feet tall

And I’m wearing a kickass suit.

Like this:

Like Loading...